International

Telecommunication Union

_________________________

Вернуться на главную Вернуться в текущую новость Перейти в базу данных

Содержание

1 MARKET AND

REGULATORY TRENDS

A vibrant

ICT sector faces tough economic times

Fixed-line service holds

steady; Mobile service grows rapidly

High-speed, broadband access

trends upward

The shift to all-IP environments

Mobile broadband markets grow

in importance

Changes in regulatory

practices

Private ownership and

competition trends

2 EXPLORING OPTIONS FOR SHARING

Why sharing, why now?

Passive and active

infrastructure sharing

3 EXTENDING ACCESS TO FIBRE BACKBONES

Complementing efforts to

improve local access

The role of government

4 MOBILE NETWORK SHARING

Passive mobile sharing

Active mobile sharing

5 SPECTRUM SHARING

6 INTERNATIONAL GATEWAY LIBERALIZATION

The importance of IGW

liberalization

7 FUNCTIONAL SEPARATION

8 INTERNATIONAL MOBILE ROAMING

9 IPTV AND MOBILE TV

Convergence: Sharing broadband

technologies

What is IPTV?

What is mobile TV?

Regulatory issues with IPTV

and mobile TV

10

END-USER SHARING

End-user computer sharing

Advanced content sharing

11

CONCLUSION

TRENDS IN TELECOMMUNICATION REFORM 2008

Six Degrees of Sharing

Summary

The Telecommunication Development Bureau (BDT) of the

International Telecommunication Union (ITU) is pleased to present the ninth

edition of Trends in Telecommunication Reform, an integral part of

ITU/BDT’s ongoing dialogue with the world’s ICT regulators. The theme of this

year’s edition of Trends – “Six Degrees of Sharing” – encapsulates new

market and regulatory strategies that optimize and maximize investment in

broadband networks and ICT equipment and services. Past editions of ITU’s Trends

in Telecommunication Reform have explored key regulatory issues such as

interconnection, universal access and licensing of domestic service provision.

These issues can be seen as making up a first wave of regulatory reform that

has been vital to growing the ICT sector in developing countries. This edition,

however, addresses a newer, second wave of regulatory reforms designed to

promote widespread, affordable broadband access.

In a way, many regulatory practices can be viewed as sharing. What

is new and innovative is their application to meet the needs of developing

countries. What is the same is that they use time-tested, pro-competition

tools, such as the regulation of essential or bottleneck facilities,

transparency, and the promotion of collocation and interconnection.

Sharing

options are also being closely examined among regulators in developed

countries. Regulators in those countries are now facing the difficult task of

encouraging efficient deployment of next-generation networks (NGNs) to meet

bandwidth-hungry consumers’ needs, while maintaining a pro-competitive

environment that fosters the emergence of new, innovative players.

This

year’s edition comprises eleven chapters under the global theme of

infrastructure sharing:

• Chapter One

provides an ICT market and regulatory overview for 2008, to set the stage for

the chapters to come;

• Chapter

Two defines sharing broadly, focusing on the many ways in which networks and

support infrastructure can be shared to promote affordable network access and

competition;

• Chapter

Three explores the mechanisms and policies for extending access to national

fibre backbones in developing countries;

• Chapter

Four discusses the sharing of mobile networks and support infrastructure, such

as towers, poles, ducts and rights of way;

• Chapter

Five moves beyond network sharing to explore new techniques and radio spectrum

sharing policies designed to meet the escalating demand for spectrum needed to

provide a growing range of wireless services;

• Chapter

Six delves into the issues driving the liberalization and sharing of

international gateway facilities, including undersea cables, cable landing

stations and satellite assets;

• Chapter

Seven turns to an exploration of functional separation as a regulatory means to

break up network bottlenecks and place retail service provision on a level

competitive footing;

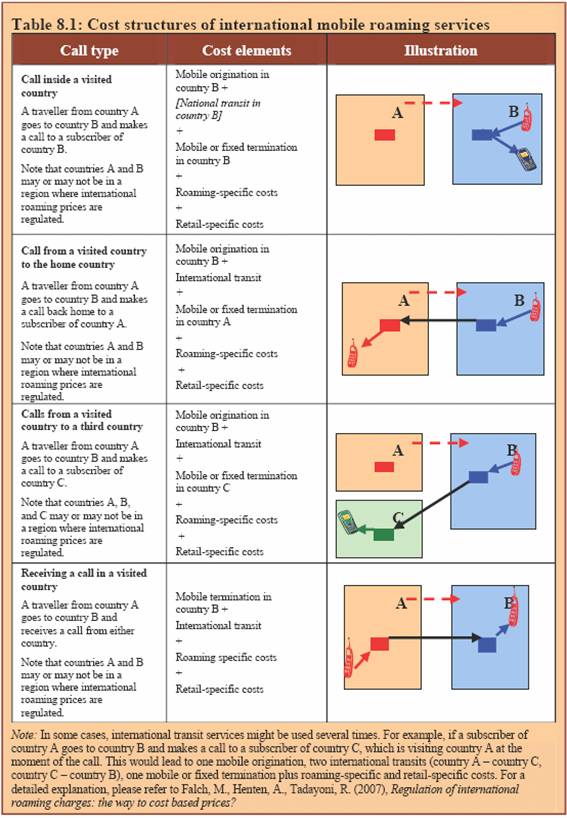

• Chapter Eight takes a novel perspective

on sharing, exploring international roaming as the “sharing” of customers by

wireless operators in different countries;

• Chapter

Nine discusses sharing in a convergence context, as Internet Protocol

television (IPTV) and mobile television evolve into new media for content

distribution;

• Chapter

Ten looks at sharing from an end-user perspective, as policy-makers and

equipment manufacturers create opportunities for ICT access by multiple users,

either sequentially or simultaneous by – effectively creating “end-user

sharing”;

• Finally, Chapter

Eleven ties it all together in a conclusion and takes a look ahead.

The year 2008 saw growth in mobile networks and subscribers rise

to an all-time high, reaching an estimated 4 billion mobile subscribers

worldwide. A growing array of broadband wireless systems are now available,

opening the way for users in developing countries to access the Internet on

mobile phones and other handheld devices. At the same time, more developing

countries were deploying national fibre backbones and backhaul networks to

transport their growing data-rich traffic. In addition, several new

international submarine cable networks were set to connect developing countries

to the global network of Internet backbones – just as a group of high-tech

entrepreneurs were working to revive plans for a constellation of broadband

satellites for the developing world.

Then came September 2008, and with it the exploding global

financial and credit crisis. The dramatic events of autumn called into question

whether the necessary financing would remain available to ensure that the

positive trends in the ICT sector would continue. Indeed, financing network

growth may have just become a lot tougher. As could be expected, the bad

financial news in September and October sparked a handful of announcements that

planned network upgrades would be postponed.

Analysts’ predictions on the impact of the financial crisis on the

telecommunication sector ranged from the optimistic – predicting only a slight

impact through 2009 – to a decline of nearly 30 per cent in capital

expenditures in the year ahead. But even the most dour prognosticators noted

that everything depended on the severity of the financial crisis, which was

still unfolding in late 2008.

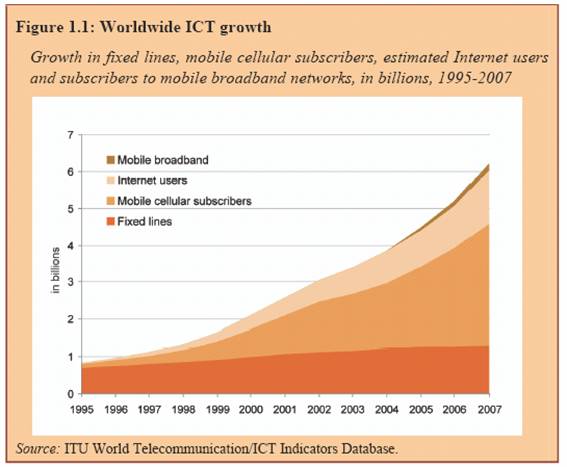

Fixed-line market penetration remains comparatively low in most

developing countries, at an average of 13 per cent by end of 2007 even though

the developing world accounted for 58 per cent of the world’s 1.3 billion fixed

phones lines in 2007. In fact, this segment of the market showed a decline in

developed countries and just a slight increase in some developing countries.

Overall, it is fair to say that fixed-line penetration worldwide stagnated in

2007.

Mobile penetration, however, continued to show high growth rates –

enough to reach an estimated 61 per cent of the world’s population (some 4

billion subscribers) by the end of 2008. Moreover, by the beginning of the

year, more than 70 per cent of the world’s mobile subscribers were in

developing countries. Five years earlier, in 2002, those subscribers had been

less than 50 per cent of the world total. Africa remains the region with the

highest growth rate (32 per cent between 2006 and 2007).

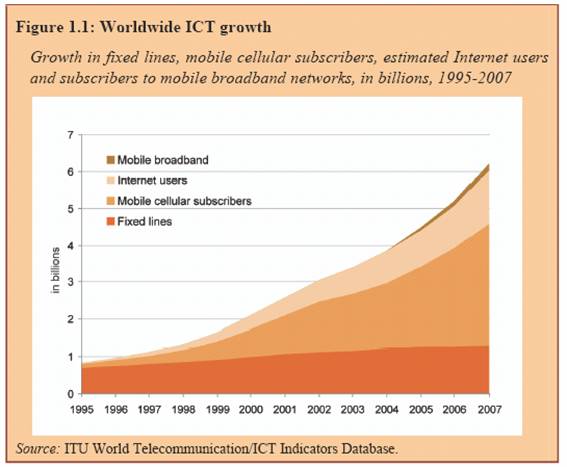

Figure 1.1:

Worldwide ICT growth

Growth

in fixed lines, mobile cellular subscribers, estimated Internet users and

subscribers to mobile broadband networks, in billions, 1995-2007

Source: ITU World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators Database.

ITU’s

Internet and broadband data suggest that more and more countries are going

high-speed. By the end of 2007, more than 50 per cent of all Internet

subscribers had a high-speed connection. Dial-up is being replaced by broadband

across developed and developing countries alike. In developing countries such

as Chile, Senegal, and Turkey, broadband subscribers represent over 90 per cent

of all Internet subscribers.

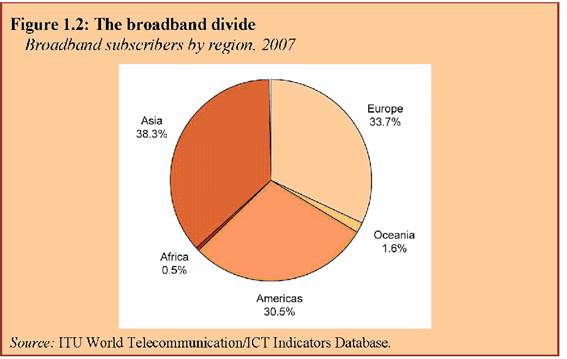

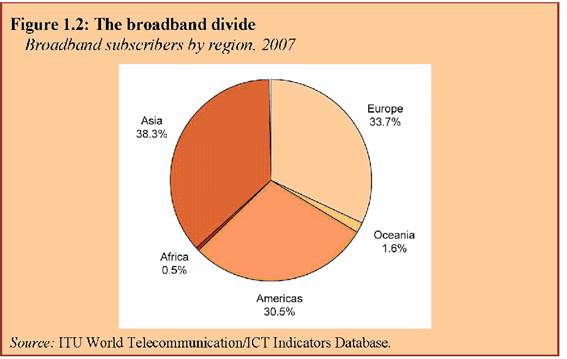

At the same

time, major differences in broadband penetration levels remain, and the number

of broadband subscribers per 100 inhabitants varies significantly between

regions. While fixed broadband penetration stood at less than 1 per cent in

Africa, it had reached much higher levels in Europe (16 per cent) and the

Americas region (10 per cent) by the end of 2007.

The difference in the uptake of

broadband is also reflected by the regional distribution of total broadband subscribers

(see Figure 1.2). Despite significant broadband uptake in developed countries,

a vast majority of developing countries still lag behind, especially those with

low-income economies.

Figure 1.2: The

broadband divide

Broadband

subscribers by region, 2007

Source: ITU World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators Database.

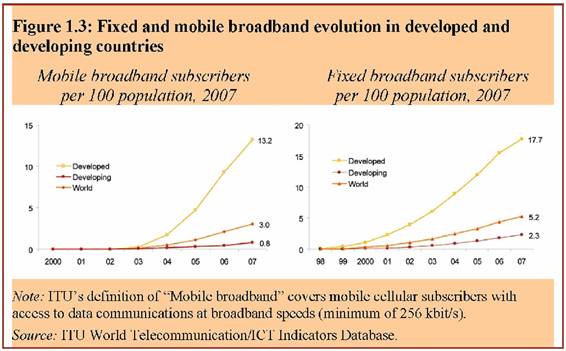

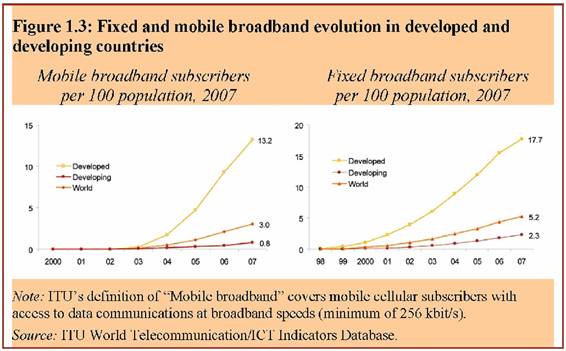

Figure 1.3:

Fixed and mobile broadband evolution in developed and developing countries

Mobile broadband

subscribers Fixed broadband subscribers per

100 population, 2007 per 100 population, 2007

Note: ITU’s

definition of “Mobile broadband” covers mobile cellular subscribers with access

to data communications at broadband speeds (minimum of 256 kbit/s). Source: ITU

World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators Database.

The shift to all-IP environments

Probably

the best example of the “all-IP” move is the rise of

Voice-over-Internet-Protocol (“VoIP”) services. In the last few years, VoIP

services have continued to grow strongly. Even if they were not as “disruptive”

to traditional telephony as had been predicted, VoIP offerings have proved to

be some of the most successful Internet applications. Over the past two years,

the market presence of VoIP has surged forward, although at a slower growth

rate than in 2005. More importantly, it is steadily replacing traditional

public switched telephone network (PSTN) lines in many developed and some

developing countries.

Both

in France and Japan, about one-third of all fixed lines were VoIP lines at the

end of 2007. According to some market analysts, the global number of VoIP

subscribers reached 80 million in 2008. It is worth noting that business users

constitute an increasing share of the total number of subscribers worldwide. Of

course, the regional distribution of those subscribers varies, depending on the

cost of traditional fixed-line communications as well as the regulatory

treatment of VoIP and of the international gateway for PSTN long-distance calls.

Today,

a number of mobile markets, both in developed and developing economies, are

saturated or close to saturation, whereas broadband penetration rates are still

relatively low in many countries. The combination of these two factors has

given a major push to the rise of mobile broadband offerings over the last

year. The number of mobile broadband subscribers reached 167 million at the end

of 2007, driven by 18 per cent growth since 2006. The market is being stoked by

robust competition among new and emerging technologies, such as the 2.5G and

3G, as well as the emerging “3.5 G” or 4G families of technologies: high-speed

packet access (HSPA), WiMAX, and long-term evolution (LTE).

The

first wave of sector reforms in developing countries, starting in the late

1990s, attempted to create more transparent and stable legal and regulatory

frameworks, with an emphasis on establishing national regulatory authorities

and opening certain market segments, such as mobile voice, to competition. The

goal was to attract investment and make progress toward universal access to

basic telecommunication services. Drastic changes in the sector have since

flowed from technological innovation, convergence of services, and growing

competition. These changes may now require a further regulatory shift to open

more market segments to competition and update licensing and spectrum

management practices in order to foster growth in broadband networks and

converged services. A rise in competition and new service providers will also

require an enhanced focus on dispute resolution.

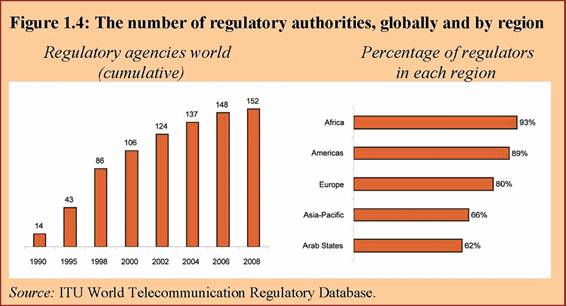

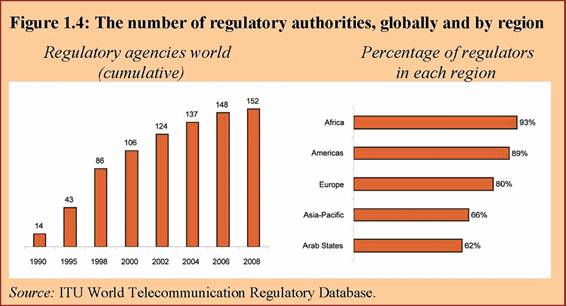

As

of October 2008, 152 countries had created a national regulatory authority for

their ICT and telecommunication sectors. Africa now has the highest percentage

of countries with a separate sector regulator (93 per cent) followed by the

Americas (89 per cent) and Europe (80 per cent). The Arab States and

Asia-Pacific number 66 per cent and 62 per cent, respectively (see Figure 1.4).

Since 2007, two new ICT regulators had been created: the Regulatory Authority

for Posts and Telecommunications in Guinea and the Vanuatu Independent

Telecommunications Regulator. Two additional agencies were being established in

the Arab States and at least one more was planned in Africa.

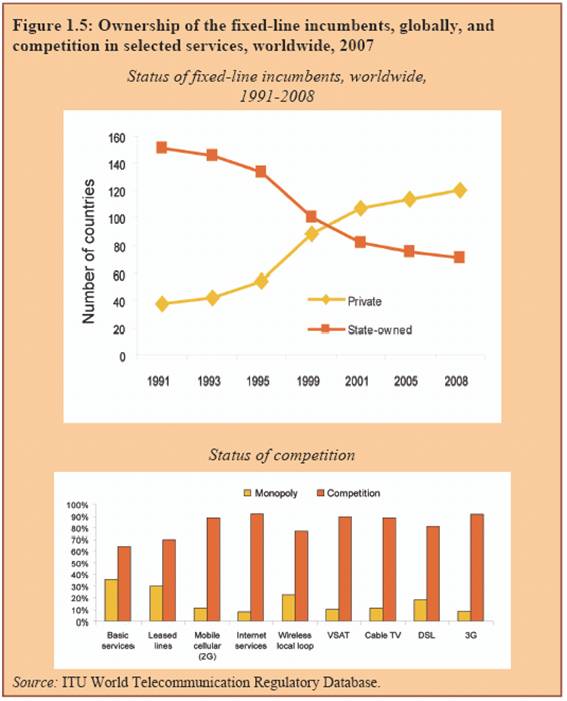

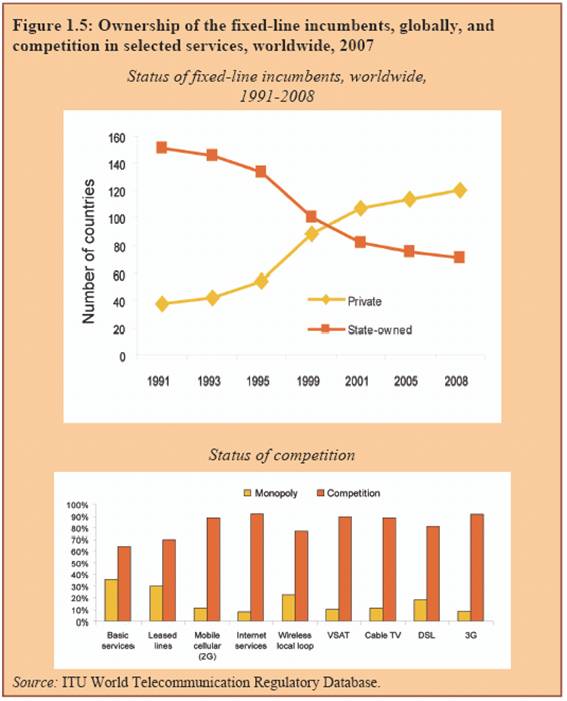

By mid-2008, 125 ITU member countries had a privately-owned,

or partially privatized, national fixed-line incumbent (see Figure 1.5). The regions

with the highest percentage of private ownership are Europe78 per cent), the

Americas (74 per cent), and Asia-Pacific (53 per cent. Although a majority of

countries in Africa and in the Arab States still have state-owned incumbents

(53 per cent and 52 per cent, respectively, a number of countries in these

regions have embarked on the privatization pa

Algeria,

Guinea and Mali have announced plans to privatize their incumbent operators in

the coming year. Will these privatizations suffer from the current global

economic and financial crisis? While it is hard to predict the long-term impact

this crisis will have on the ICT sector, there is certainly the possibility

that it will affect the flow of capital into privatizations in developing

countries.

Figure

1.5: Ownership of the fixed-line incumbents, globally, and competition in

selected services, worldwide, 2007

Markets

steadily continue to open to competition. Mobile (2G as well as 3G and beyond)

and Internet services continue to be the most competitive markets, while

fixed-line services are increasingly becoming competitive, as well. Only 40

countries had authorized competition in the provision of basic

telecommunication services in 1997, but a decade later the number had risen to

about 110 countries.

Encouraging

effective competition has proved to be the best way to promote ICT sector

development and consumer accessibility. Liberalization of access to

international facilities is another trend taking place in developing countries,

especially in Africa. Countries that have liberalized international gateways

have seen prices fall and quality of service improve. Liberalization includes

licensing or authorization of multiple players for the provision of

international gateway services and opening up cable landing stations to

competition.

Looking at

ensuring competitive access to essential facilities, one of the recent

developments in policy-making is the concept of “equivalence of inputs”, which

holds that all market players should enjoy the same access to essential

facilities.7 Remedies such as accounting separation appear

inadequate, in some cases, to ensure non-discriminatory access to incumbents’

networks. The European Commission, for example, is searching for more effective

measures – including functional separation as a last-resort remedy. This is

discussed in greater detail in Chapter 7 of the 2008 edition of Trends.

Why sharing, why now?

The

single biggest reason to adopt sharing is to lower the cost of deploying broadband

networks to achieve widespread and affordable access to ICTs. Developing

countries can leverage the technological, market and regulatory developments

that have led to an unprecedented uptake in mobile voice services to promote

widespread and affordable access to wireless broadband services and IP-based

national fibre backbones, as well.

Promoting

widespread broadband access costs real money. Deploying mobile base stations or

fibre backbone networks to reach rural areas may be uneconomical if each

service provider must build its own network. Likewise, laying fibre to every

home, building or street cabinet – the goal of many developed countries – may

be unattainable if operators act alone. Companies can, however, share some

infrastructure but compete in providing services. With an effective legal and

regulatory framework and the right incentives, the critical factor in creating

new, affordable broadband access and backbone networks will be government

willpower.

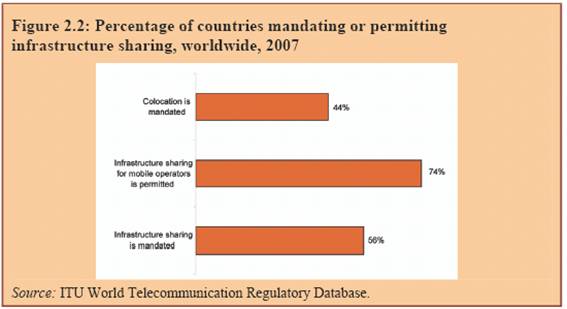

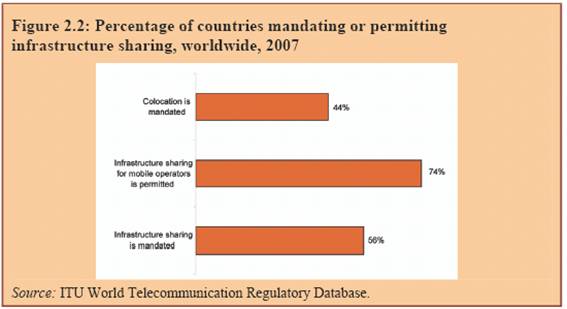

Sharing

does not mean abandoning market liberalization or universal access practices.

On the contrary, further market liberalization is required, for example, in

international gateway markets, and to allow a new range of market players to

meet the pent-up demand for broadband services. Universal access practices also

can be refined and improved. All sharing practices – and infrastructure

sharing, in particular – are integral parts of a competitive regulatory

framework. Infrastructure-sharing regulations, whether mandatory or optional,

are usually included in a country’s interconnection framework, although they

are occasionally contained in operators’ licensing agreements.

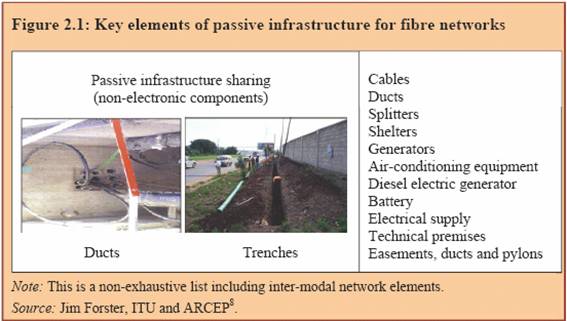

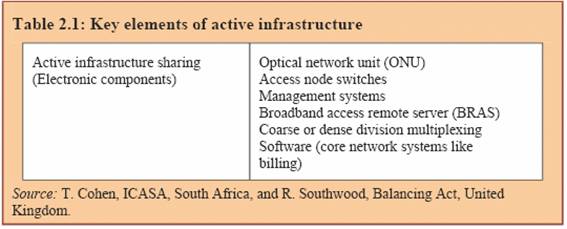

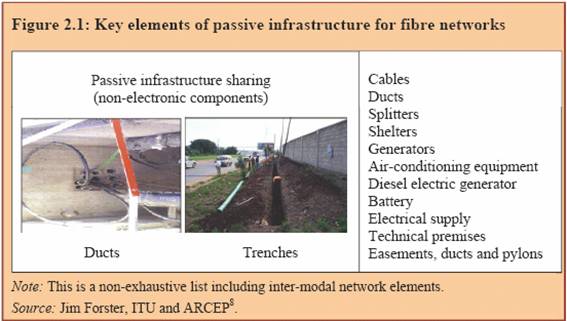

Infrastructure

sharing takes two main forms: passive and active. Passive infrastructure

sharing allows operators to share the non-electrical, civil engineering

elements of telecommunication networks. This might include rights of way or

easements, ducts, pylons, masts, trenches, towers, poles, equipment rooms and

related power supplies, air conditioning, and security systems.

These facilities and systems all vary, of

course, depending on the kind of network. Mobile networks require tower sites,

while fibre backhaulbackbone networks require rights of way for deploying cables,

either on poles or in trenches. International gateway facilities, such as

submarine cable landing stations, can be opened for collocation and connection

services, allowing operators to directly compete with each other in the

international services market. Access to physical ducts, masts/poles (in the

case of power transmission lines), and rights of way are key potential passive

network elements for encouraging the rollout of national fibre infrastructure

through sharing. This has two aspects, one relating to cost and the other

affecting speed of action. National governments, municipalities state-owned

enterprises frequently charge considerable sums of money for rights of way that

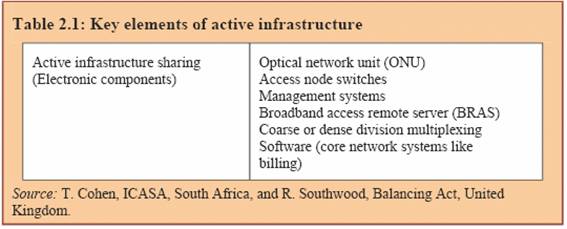

allow operators to carry out physical trenching of ducts. Active

infrastructure sharing involves sharing the active electronic

network elements – the intelligence in the network – embodied in base stations

and other equipment for mobile networks and access node switches and management

systems for fibre networks. Sharing active infrastructure is a much more

contested issue, as it goes to the heart of the value-producing elements of a

business. Many countries have restricted active infrastructure sharing out of

concern that it could enable anti-competitive conduct, such as collusion on

prices or service offerings

These concerns remain

valid, but they have to be weighed against advances in technology and

applications that enable service providers to differentiate their offerings in

the market. In addition, for some remote and less accessible areas, the risks

of active infrastructure sharing have to be balanced against the alternative of

having no services at all.

Regulators may at least

allow active infrastructure sharing for a limited time, until demand for ICT services

grows to support multiple network operators. Regulators and policy-makers may

elect to adopt only one kind of infrastructure sharing, or they can implement

many options simultaneously. Some regulatory frameworks today may authorize

passive infrastructure sharing, for example, while prohibiting active

infrastructure sharing. Some regulators simply have not addressed the issue –

neither explicitly authorizing nor prohibiting infrastructure sharing.

A

critical aspect of promoting wider broadband use is ensuring that national

fibre infrastructure is affordable. While competition at the international

level has often driven down the price of bandwidth, national bandwidth prices

in developing countries are set by one or two providers and, as a result, often

remain high.

Increasingly,

the sharing of infrastructure by telecommunication operators, based on a model

of open access, is one option attracting greater policy attention. While

liberalized markets already have numerous models of infrastructure sharing,

such as collocation, national roaming and local loop unbundling, other forms of

sharing are also starting to emerge that involve sharing both the “passive” and

“active” elements of the network. However, effective enabling regulation and

policy are critical to facilitate such arrangements.

Infrastructure-sharing

regulation and policy must address two broad issues that are often viewed as

the stumbling blocks to speedy roll-out of national telecommunication

infrastructure:

�.

• Opening up access to “bottleneck” or

“essential” facilities, where a single dominant infrastructure operator

provides or leases facilities.

�.

• Promoting market investment in deploying

high-capacity infrastructure to unserved or underserved areas.

Box 3.1: What is open access?

Open access means the creation of competition in all layers of the network,

allowing a wide variety of physical networks and applications to interact in an

open architecture. Simply put, anyone can connect to anyone in a

technology-neutral framework that encourages innovative, low-cost delivery to

users. It encourages market entry from smaller, local companies and seeks to

prevent any single entity from becoming dominant. Open access requires

transparency to ensure fair trading within and between the layers, based on

clear, comparative information on market prices and services.

Source: InfoDev, 2005.

Broadband services and the infrastructure on which they depend

have become recognized as an essential input to business, education, health

care and participation in the information economy. A developed broadband

infrastructure is a pre-requisite for increased investment in any

community.

In economic terms, access to a national broadband fibre network is

as important a priority as building an effective national transportation

network. Given the central role that ICTs play in the information economy, many

argue that broadband access is a “public good” similar to roads and railways.

Without broadband access, developing countries run the risk of enlarging the

“digital divide” and becoming second- or third-class nations within the global

order. Having competitively priced national broadband access has become an

important criterion of global competitiveness.

Government has

a key role to play in facilitating the most effective use of infrastructure

assets, identifying parts of the country where there are gaps, and getting

coverage extended to them. Moreover, governments, together with regulators, can

establish effective regulatory frameworks and regimes that promote effective

use and sharing of networks. Designing a regulatory framework may depend on

whether the national backbone provider competes with other service providers

for end users (and therefore has every incentive to block competitors) or

whether the backbone provider does not serve end users (and therefore has every

incentive to sell as much capacity as possible to those who do). In the former

case, the regulatory response could be to treat the backbone network as an

essential facility, including regulating prices for access as well as

establishing uniform collocation and connection terms for all market players

seeking access to the backbone. In the latter, it may be sufficient to revise

licensing frameworks to authorize one or more new entrants to enter the

backbone market and to work with local government officials to secure rights of

way to lay the fibre backbone network. Local governments could be encouraged to

provide rights of way, for example, in exchange for connecting schools and

hospitals to the high-speed backbone network.

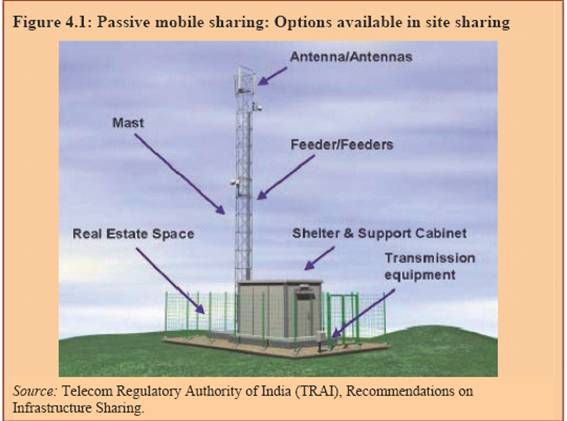

Rolling

out mobile networks involves intensive investment and sunk costs, potentially

leading to high mobile-service prices. Mobile infrastructure sharing is one

alternative for lowering the cost of network deployment, especially in rural,

less populated or economically marginalized areas. Mobile infrastructure

sharing may also stimulate the migration to new technologies and the deployment

of mobile broadband networks, which are increasingly seen as the best way to

make broadband Internet access available to the majority of the world’s

population. Mobile sharing may also enhance competition among operators and

service providers.

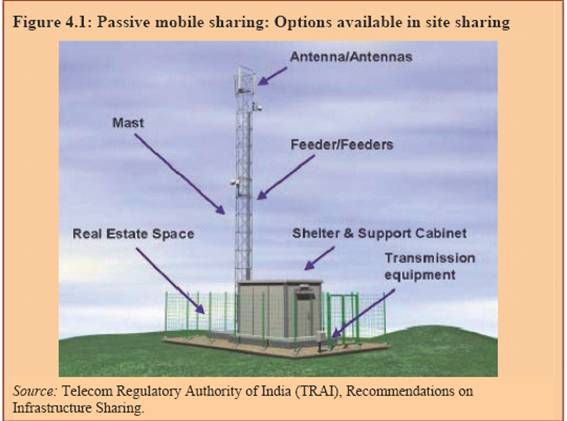

For mobile

sharing, the passive elements are defined as the physical network components

that do not necessarily have to be owned or managed by each operator. Instead,

these components can be shared among several operators. The provider of the

infrastructure can either be one of the operators or a separate entity set up

to build and operate it, such as a tower company. The passive infrastructure in

a mobile network is composed mainly of:

�.

• Electrical or fibre optic cables;

�.

• Masts and pylons;

�.

• Physical space on the ground, towers,

roof tops and other premises; and

�.

• Shelter and support cabinets, electrical

power supply, air conditioning, alarm systems and other equipment.

A collection of passive network equipment in one structure for

mobile telecommunications is generally called a “site.” Therefore, when one or

more operators agree to put their equipment on (or in) the same site, it is

called “site sharing” or “collocation.”

In

addition to sharing passive infrastructure, operators may also share active

elements of their wireless networks. The “active elements” of a wireless network

are those that can be managed by operators, such as antennas, antenna systems,

transmission systems and channel elements. Operators may share those elements

and keep using different parts of the spectrum assigned to them. Although

active infrastructure sharing is more complex, it is technically possible.

Equipment manufacturers can supply packages that have expressly been designed

for active mobile sharing.

It is clear that network-sharing agreements may

benefit operators and the general public. They help operators avoid costs for

building or upgrading redundant network sites and allow them to gain additional

revenue streams from leasing access. Operators also can achieve considerable

savings in rent, maintenance and transmission costs. They may also achieve

economies of scale by combining operating and maintenance activities.

Network sharing may further help operators to

attain better coverage, since they may choose to use only those sites that provide

deeper and better coverage, decommissioning sites with poor coverage

possibilities. Network-sharing agreements may also bring substantial

environmental benefits, by reducing the number of sites and improving the

landscape.

There are obstacles to be overcome, of course,

when dealing with network-sharing agreements. From an economic and practical

point of view, network sharing is a complex process that requires substantial

managerial resources. Therefore, regulators should analyse the potential benefits

to be generated by network sharing on a case-by-case basis, taking into account

the specific characteristics of each market involved.

Spectrum

sharing encompasses several techniques – some administrative, some technical

and some market-based. Spectrum can be shared in several dimensions: time,

space and geography. Limiting transmission power is also a way to permit

sharing among low-power devices operating in the spectrum “commons” – as with dynamic

spectrum access, which takes advantage of power and interference reduction

techniques. Sharing can also be accomplished through licensing and/or

commercial arrangements involving spectrum leasing and trading.

As the demand

for spectrum increases and available frequency bands become more congested,

especially in densely populated urban centres, spectrum managers are exploring

diverse paths to sharing frequencies:

• Using administrative methods, including

in-band sharing;

• Creating new, secondary market

mechanisms, such as spectrum leasing and spectrum trading;

• Adopting unlicensed or spectrum “commons”

approaches; and

• Encouraging use of low-power radios or

advanced radio technologies, such as ultra-wideband or multi-modal radios.

Increasingly, spectrum managers will have to resort to new

techniques and technologies to allow spectrum sharing. In theory, all bands can

be shared, using combinations of administrative means (setting geographic

separation buffers and channelization plans) and technical solutions (SDR and

cognitive radio, as well as smart antennas). Power limits and more robust

receivers are also key factors.

Interference,

however, cannot be eliminated and so must be managed. Identifying interference

management models that support spectrum sharing under either administrative, market-based

or spectrum “commons” approaches will remain an ongoing requirement and

challenge for spectrum managers. Their goal is to develop an appropriate regime

that protects user rights and finds the right balance for flexibility and

innovation, along with service neutrality. Finding that balance and structuring

the appropriate response will continue to be debated. Spectrum managers and

regulators can successfully implement spectrum sharing by combining vision,

commitment and careful planning, altering their spectrum allocation and

assignment policies to permit greater flexibility and access to spectrum

resources.

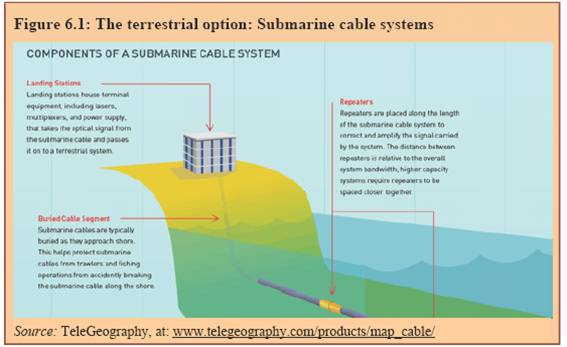

Broadband Internet access has become commonplace and increasingly affordable

in many areas of the world, but that is not yet the reality for most residents

of developing countries. Broadband services are either unavailable, or they are

almost prohibitively expensive, constituting a barrier to meaningful entry into

the global information economy. Yet, without greater demand, the market for

broadband services in many developing countries will remain stunted, crippling

the broad-based social and economic growth that comes from joining the

information society.

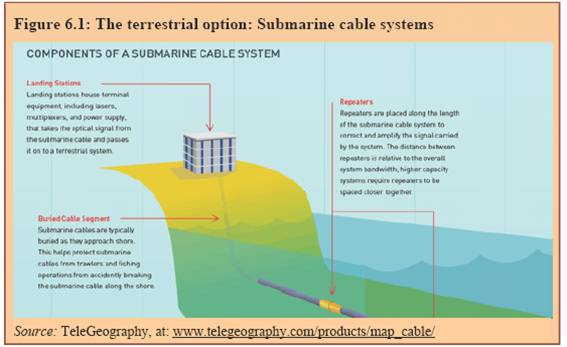

Figure 6.1:

The terrestrial option: Submarine cable systems

Source: TeleGeography,

at: www.telegeography.com/products/map_cable/

High prices for broadband access are tied

to a lack of access to international network capacity. One way that countries

can cut through the capacity conundrum is through liberalization of

international gateway (IGW) facilities. The international cable and satellite

systems that link multiple countries reach choke points as they are “landed”

within each destination. These choke points are the facilities that aggregate

and distribute international traffic to and from each country. In some

countries the IGW is controlled by a fixed-line incumbent that charges monopoly

prices for all international traffic, including Internet traffic, making services

too expensive for end users and stifling demand.

Liberalizing

access to these gateway facilities through infrastructure sharing can lower

infrastructure costs while multiplying the amount of international capacity

available to operators. The result can be a rapid ramp-up of international

traffic, coupled with lower prices for international communications. More

affordable services, in turn, can generate greater demand, resulting in more

consumers on the network.

Functional

separation is one of the most drastic and potent regulatory remedies in a

regulator’s arsenal. There are enormous implications, not just for the

incumbent but also for the regulatory agency in charge of its implementation

and enforcement. This chapter explores functional separation, its ramifications

and when, how – or indeed, whether – to implement it.

Functional

separation is a recent response by regulators and governments to the serious

problem of anti-competitive, discriminatory behaviour by incumbents. It has

arisen from a concern that existing rules and remedies are inadequate to deal

with the problem. In particular, the focus of concern is often the incumbent’s

ownership of bottleneck network infrastructure and its abuse of that control to

harm competitors’ ability to provide broadband services.

Functional

separation is sometimes

also known as operational separation. The term applies to the fixed-line

business of incumbent operators, and it entails:9

�.

• Establishing a new business division,

which is kept separate from the incumbent’s other business operations;

�.

• Capitalizing and empowering this new,

separate business division to provide wholesale access to the incumbent’s

non-replicable (or bottleneck) assets, which competitors need in order to compete

with the incumbent in downstream retail markets; and

�.

• Requiring the separate wholesale division

to supply network access (and support services) to competitors, along with the

incumbent’s own, remaining retail divisions, on a non-discriminatory basis.

Often, the incumbent sets up not just a network operations

division, but also a wholesale services division, which then can purchase

access to the bottleneck assets and resell them to retail operators. The bottom

line is that wholesale access and services are made available to the

competitors and the incumbent’s retail operations on an equal basis.

So

far, implementation of function separation has been limited mainly to a small

number of developed countries, although it appears to be gaining currency in

several other countries.

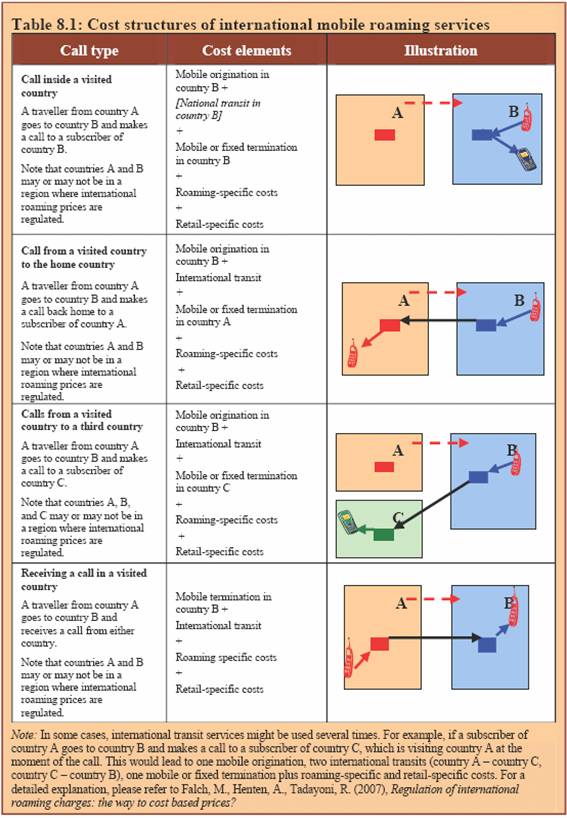

International

mobile roaming services allow customers of one mobile network operator to use

mobile services when travelling abroad. These services are enabled by a direct

or indirect (either through a broker or aggregator) relationship between the

“home” and “visited” operators. In effect, international roaming is a form of

sharing. Operators can multiply the range of their service offerings around the

world by essentially borrowing access to operators’ networks in other

countries. They can then give their customers seamless service wherever they

travel – at a price, of course.

International

mobile roaming revenues now constitute a significant portion of mobile

operators’ revenues and profits. Telecommunication analysts estimate

that international mobile roaming generates approximately 5-10 per cent of

operators’ revenues globally (in some cases up to 15 per cent), and constitute

an even bigger slice of their profits. Because customers lack any viable

alternative to international mobile roaming services (especially those who must

make mobile international calls, such as business users), customers continue to

use these services even in the face of high tariffs. Therefore, the subject of

international mobile roaming charges is now of great interest to many

governmental organizations.

After

analysing international mobile roaming costs and actual prices charged,

regulators might choose one of the following strategies:

�.

• No direct regulation

of any international mobile roaming tariffs;

�.

• Regulating

wholesale international mobile roaming rates only;

�.

• Regulating

retail international mobile roaming charges only;

�.

• Regulating

both wholesale and retail international mobile roaming rates.

The

different strategies regulators can choose to address international mobile

roaming charges are analysed in Chapter 8 of this edition of Trends. It

also identifies the pros and cons of each of these strategies recognizing that

upcoming next-generation networks, and the move to mobile IP networks, could

change the status quo, making the roaming problem less relevant

For countries struggling with the appropriate means and incentives

to foster broadband development, the introduction of video services by fixed

telecommunication providers may prove to be a key facilitator for such

deployment. Traditional telecommunication operators are upgrading their

facilities to obtain more bandwidth capacity in order to offer video services

and acquire a new revenue stream. These new video offerings are positively

affecting the roll-out of new broadband networks. As a result, the provision of

IPTV services has the potential to not only increase competition in the video

marketplace, but also to advance the broadband access goals of many countries.

Mobile television (mobile TV) is also being introduced in a number

of countries. Unlike most video services offered by 3G mobile operators, mobile

TV allows a user to view live television channels, not just downloads. For

mobile providers looking for ways to maintain and increase growth, mobile TV is

a new avenue to increase their average revenue per user (ARPU) through added

content and services.

IPTV is defined as the provision of video services (for example,

live television channels, near video-on-demand (VoD) or pay-per-view) through

an IP platform. However, some define IPTV services to encompass all the

possible functionalities that can be provided over an IP platform. For example,

some equate IPTV services with multimedia services, a category that can include

television, video, audio, text, graphics, and data. This encompasses not only

one-way video broadcasting services but also ancillary interactive video and

data services, such as VoD, web browsing, advanced e-mail, and messaging

services.

Mobile TV is

the wireless transmission and reception of television content

– video and voice – to

platforms that are either moving or capable of moving. Mobile TV allows viewers

to enjoy personalized, interactive television with content specifically adapted

to the mobile medium. The features of mobility and personalized consumption

distinguish mobile TV from traditional television services. The experience of

viewing TV over mobile platforms differs in a variety of ways from traditional

television viewing, most notably in the size of the viewing screen.

There

are currently two main ways of delivering mobile TV. The first is via a two-way

cellular network, and the second is through a one-way, dedicated broadcast

network. Each approach has its own advantages and disadvantages.

The

introduction of IPTV and mobile TV services presents regulatory issues-linked

to convergence of the ICT and broadcasting sectors. IPTV and mobile TV provide

new platforms and devices to distribute digital television and multimedia

offerings. But regulators are often uncertain whether the new offerings should

be considered broadcasting, telecommunication, or information services – or

whether they should be exempt from regulation altogether.

Operators of

IPTV and mobile TV services, however, need a clear set of rules that will

create the adequate environment for investment and deployment of their networks

and services. Regulatory classifications will have a direct impact on issues

such as market entry, licensing, content regulation, ownership requirements,

geographic coverage (nationwide, regional or local licences), regulatory fees,

and other obligations.

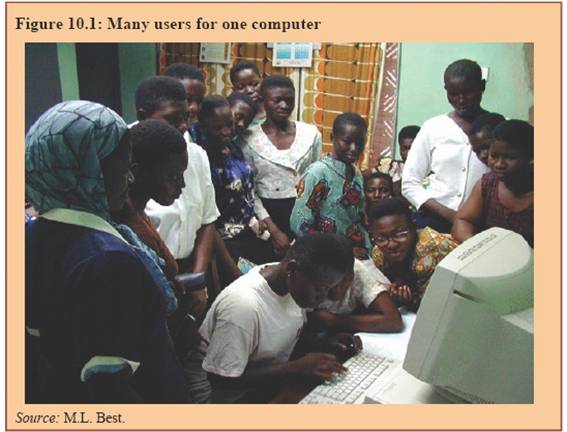

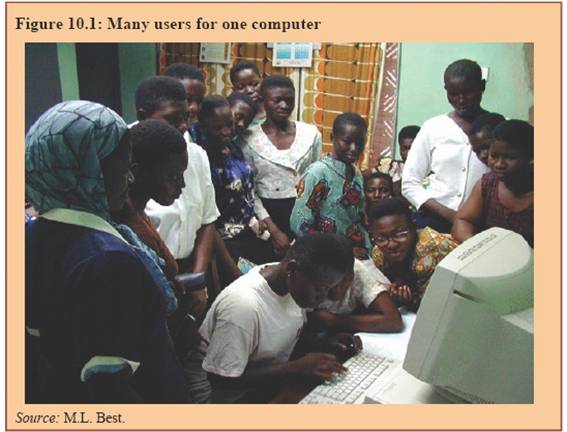

Sharing ICT technologies is a common behaviour among people around

the planet. People share for a variety of reasons ranging from economic to pedagogical

concerns. When they do it intentionally, as part of the usual or normal

operation of a service or application, we call this end-user sharing. To

be sure, this kind of sharing is commonly a by-product of lower income levels,

weak infrastructures, scarcity, or want. But this does not hide the fact that

technologies are programmed for sharing.

Figure 10.1:

Many users for one computer

Source: M.L. Best.

End-user telephone sharing has been the most

common form of two-way communication sharing among end users – at least in the

form of public payphones. Until recently, public phone boxes were common in

low- and high-income contexts alike. But today, in many countries, mobile

phones have increasingly been replacing public payphones although public phone

facilities remain common in many low- and middle-income settings. End users in

most African countries are likely, in the foreseeable future, to continue

obtaining telephony access primarily through public access facilities – whether

they are booths managed by telecommunication operators or privately-managed

tele-shops.

Some analysts argue that sharing mobile phones can act “as an

infrastructure service; a financial sector service (virtual currency, electronic

accounts or banking); a market, weather and health information exchange

mechanism; and an investment sector service.” Basic text messaging is perhaps

the simplest and most common value-added phone service. Today, tens of billions

of SMS text messages are sent every month.

A promising area for mobile end-user sharing is financial and

banking services, often referred to as “m-commerce”. Basic mobile financial

serv-ices could include access to secure savings accounts, non-interest credit

opportunities, currency management, fund transfers and cash delivery.

M-commerce has the potential of removing the biggest obstacle for commercial

banks to serve low-income communities: the high transaction costs associated

with very modest-sized accounts. Mobile banking (and digital banking, more

broadly) has been shown to significantly lower transaction costs compared with

brick-and-mortar banking.

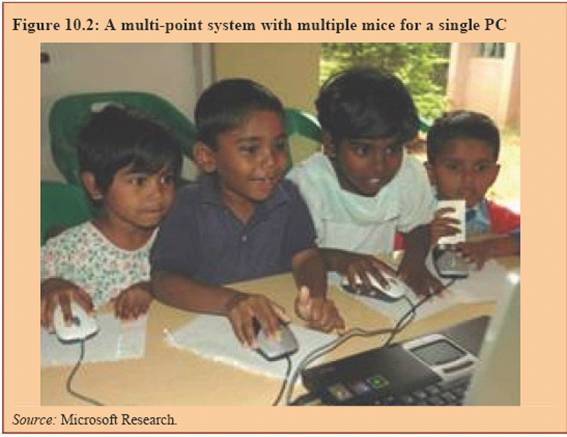

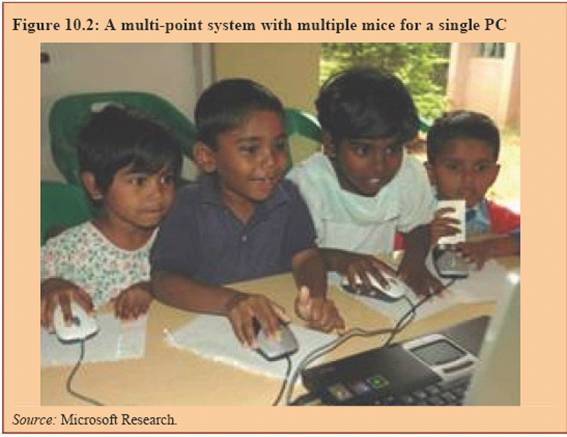

Figure 10.2: A multi-point system

with multiple mice for a single PC

Source: Microsoft

Research.

Many aspects of computer system design discourage end-user

sharing. Indeed, the term personal computer illustrates how hostile to

sharing these technologies may be. But some researchers are attempting to turn

the personal computer into something that can be more easily shared by

communities of users.

Moving

beyond the sharing of physical hardware, there is a world of computer-mediated,

Internet-enabled websites and applications. These are virtual “places” where end

users share content and build cybercommunities on popular, so-called social

network sites. End users have come to share personal narratives, World-Wide-Web

bookmarks and other online content, pictures, movies,

online encyclopedias,2and, really, anything and everything

about themselves. Additionally, many of these technologies are also available

on mobile platforms. But the worldwide reach of each of the major social

network players is hardly uniform.

Here again,

regulators have a critical role to play in the development of robust end-user

sharing experiences. The properties of sharing are explored in greater detail

in Chapter 10 of this edition of Trends, as well as the ways that ICTs

can encourage and enhance sharing, business models and applications that are

predicated on end-user sharing and the role of the regulator as it relates to

sharing.

The

forward-looking exploration of sharing mechanisms may serve the global ICT sector

well, especially in the face of the potential broad economic downturn. Sharing

offers numerous potential business strategies and regulatory approaches

designed precisely to make more economically efficient use of network assets.

At

its best, an approach based on the Six Degrees of Sharing will lower

market-entry barriers and reduce and share network build-out and maintenance

costs for investment in ICT networks and services. The idea is to move toward a

second wave of sector reform in developing countries. There is a growing

recognition among regulators – reflected in the discussions of sharing – that

the rise of viable competition, and the extension of universal access – will

depend on a savvy application of new rules and mechanisms based on the real-world

circumstances found in each market. This would be true in any economic scenario

– but it is even more crucial in the current economic environment.

Initially

developed as a set of strategies to extend broadband network access in

developing markets, Six Degrees of Sharing may now have even broader appeal if,

as it appears possible, the sources of capital for network investment suffer a

temporary drought. Indeed, it may become increasingly necessary for

policy-makers and regulators to adopt sharing strategies to make their markets

that much more amenable to the shrinking pool of investment dollars. The first

wave of sector reform has demonstrated that huge pent-up demand exists for

telecommunications and ICT services, and that consumers are willing to pay for

these services no matter how small their income. This demand continues to grow

for new ICT services made possible by technological and commercial innovation.

What has changed is that potential investors will no doubt have to work harder

to attract financing. Cutting costs, by adopting the sharing strategies

explored in the 2008 edition of Trends in Telecommunication Reform,

promises to help make limited financing resources go further to make the dream

of an “information society” a reality.

_________________________

Вернуться на главную Вернуться в текущую новость Перейти в базу данных